Big Tom Right-of-Way Update

By Janice Reid

I spent 33 years studying the federally listed northern spotted owl (NSO) for the US Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station in the Roseburg Bureau of Land Management (RBLM) office. I took my position as a research scientist seriously and did not participate in the management side of federal employment. Over the years, I learned about some of the absurd federal and state rules and regulations affecting our public lands and the NSO, and it was often difficult to remain neutral when those in decision-making positions chose not to act in the public’s best interest. But, I had very little time to delve into the management documents, legal policies, and agency interactions, let alone make well-informed and legal arguments against those decisions. I left that to those with better skills and knowledge than myself. After retiring in 2019, I started to pay more attention to how agencies work. Past members of Umpqua Watersheds (UW) have brought to the public’s attention the egregious actions that unnecessarily occur on our public lands in some of our irreplaceable old forests. Legal challenges have sometimes worked, but I would like to explain what UW has been working on for the last few months that will likely make you shake your head in disbelief. This kind of situation occurs generally without public knowledge or scrutiny.

Discovering a road right-of-way (ROW) marked in one of the spotted owl core areas within the study area where I spent my entire career was disheartening. It was not on any BLM planning documents or the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF) online reporting system. With the help of our legal advisor, Angela Jensen, UW brought its concerns directly to the RBLM district manager, Heather Whitman, who gave us several details about the situation. ROWs within the O&C “checkerboard” lands are part of an agreement that dates back to the 1950s. More detail regarding this agreement can be found in the lengthy document “Guidelines for the Administration of the O&C Logging Road Right-of-Way Regulations in Western Oregon.” The ROW law predates the Endangered Species Act (ESA), the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) and other modern legislation developed to protect resources that have been exploited. Angela determined that ROW agreements were legally challenged in the past without success. Since it is not a “discretionary” federal action, BLM does not include them in their public comment planning documents. There are only three reasons whereby BLM may object to a proposed right-of-way construction; “if (1) it does not constitute the most reasonably direct route for the removal of forest products from the lands of the road builder, taking into account the topography of the area, the cost of road construction and the safety of use of such road, (2) the proposed road will substantially interfere with the existing facilities or improvements of the lands of the landowner, or (3) would result in excessive erosion to lands of the landowner.”

The timber company, Roseburg Forest Products (RFP), eventually filed a notification of road construction with the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF), whose policy for NSO resource protection is focused on currently occupied sites for protection. The NSO population, and subsequently occupied sites, have plummeted in recent years and the ODF policy interprets such sites as “abandoned.” Thus, the core area in question did not receive protection under the State Forest Practices Rules (FPR) for private landowners. As part of the ODF response to RFP, there are specific cautions about the potential “take” of the species and the need to contact the US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS). We contacted RFP directly in an attempt to reason with them. Still, they are not interested in further conversation and refuse to return our calls and letters at the local and corporate levels.

Another thing to consider about this site is that the NSO core area consists of multiple nest trees on land that is allocated as Late Successional Reserve (LSR) under the Northwest Forest Plan and is designated NSO critical habitat by the USFWS. Therefore, we needed to know how the ESA applies to private landowners whose actions occur on public land. The USFWS cannot engage RBLM because this is not a federal project. Since the road construction as proposed will bisect the four known NSO nest trees, the private landowner is responsible for contacting the USFWS. RFP has received numerous letters and phone calls from state employees and UW about the necessity of contacting the USFWS for a possible incidental take of a threatened species. “Take” includes the destruction of habitat. Since the landowner has not yet contacted the USFWS, we have formally requested that the USFWS investigate a potential “take” situation under Section 9 of the ESA.

So, let’s look at the specifics of the site and the reasons why RBLM could object to the ROW application.

Photo 1. The location of the ROW (blue line) is NW of Drain and can be accessed via the Tom Folley Road network. The proposed road will intersect with Upper Tom Folley Rd. The red line is our suggested route.

In their documentation for issuing the permit, the RBLM manager determined that “the road construction was the most reasonably direct for the removal of forest products from the lands of the road builder, taking into account the topography of the area, the cost of road construction, and the safety of use of such road.” The topography map in Photo 1. shows the proposed road (blue line) running through the owl core area on public land (0.71 miles). The red line is what could be utilized to access their land from North Fork Tom Folley Spur Rd (~0.5 miles) (Photo 1). This refutes the BLM’s claim that the route is the “most reasonably direct.”

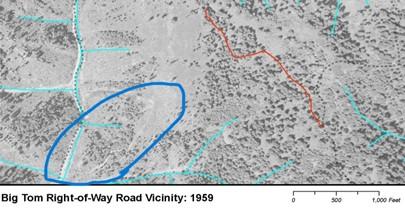

But let’s look at the rest of the criteria: “taking into account topography.” We contend that the topography of the first segment of the proposed road is as steep, or steeper, as the shorter road section in red. When reviewing the area to the south, it is clear that segments occur on much steeper terrain. Topography is not an issue: historical photos (Photo 2) show that mechanical equipment could traverse the landscape without needing access from the public land.

Photo 2. 1959 aerial with proposed (red line) road on public land and past bulldozed road on private land (circled in blue). Double dashed lines are currently maintained roads.

The cost of construction is another criterion. Road building costs are offset in part by the trees removed and taken to the mill for processing. However, in this case, the permittee cannot offset the cost of road construction by extracting the largest trees. Page 65 of the 2016 BLM Resource Management Plan (RMP) states that with respect to right-of-ways in LSR “For any trees that are both ≥ 40” DBH and that the BLM identifies were established prior to 1850, retain cut trees in the adjacent stand as down woody material. The BLM identification of trees established prior to 1850 may be based on any of a variety of methods, such as evaluation of bark, limb, trunk, or crown characteristics, or increment coring, at the discretion of the BLM.” We observed that many of the trees within the proposed construction corridor are likely to be over 40 inches DBH during ground-truthing.

The 2016 RMP is also clear in the management direction for NSO habitat. Page 64 states that the agency should “Manage for large blocks of northern spotted owl nesting-roosting habitat that support clusters of reproducing spotted owls…” and also “Protect stands of older, structurally-complex conifer forest. Such stands are a subset of, and represent the highest value, northern spotted owl nesting-roosting habitat.” It is clear that road-building through large blocks of NSO habitat, especially core areas on LSR lands, is counter to the management direction. Given that the proposed road further fragments NSO habitat, it is hard to justify that this is the “most reasonably direct route.” Furthermore, it is not the direction of the Biden Administration which, on April 22nd, directed agencies to identify and inventory mature and old-growth forests critical to addressing our climate crises while simultaneously identifying threats to their retention. To continue building roads and extracting mature, old-growth trees in the process is a grave threat and is indeed an abuse of these ROW agreements.

Even though the BLM cannot make the private company comply with the ESA, the solicitor in a failed court case indicated that “As part of its general duty to promote conservation of the species, the BLM should, however, alert permittees to particular situations which may result in an incidental take and to the prohibitions and enforcement provisions contained in the ESA.” The BLM did not follow the solicitor’s recommendation by alerting RFP to these facts.

In the state of Oregon’s recent Draft Habitat Conservation Plan, much emphasis is placed on LSR forests as secure habitat for late-successional species. Yet, state policies leave those reserves at risk. ODF could make a policy change in the way administrative rules apply to species such as the NSO and prioritize the habitat for protection instead of focusing on occupied sites.

For this situation, four entities could act to prevent the destruction of NSO habitat. The RBLM could object to the ROW because it is not the most direct route. ODF could change its policy to protect NSO habitat regardless of occupancy. USFWS could investigate the “take” under section 9 of the ESA. Most importantly, RFP could choose to access their property without destroying a federally protected reserve. Will any of these entities act to prevent the continued destruction of older forests on public reserve land, or will it be up to us to rise to challenge the existing laws? At least we will try; you can count on that.