Forest Management and Wildfire: Myth Meets Reality

Here we go again…

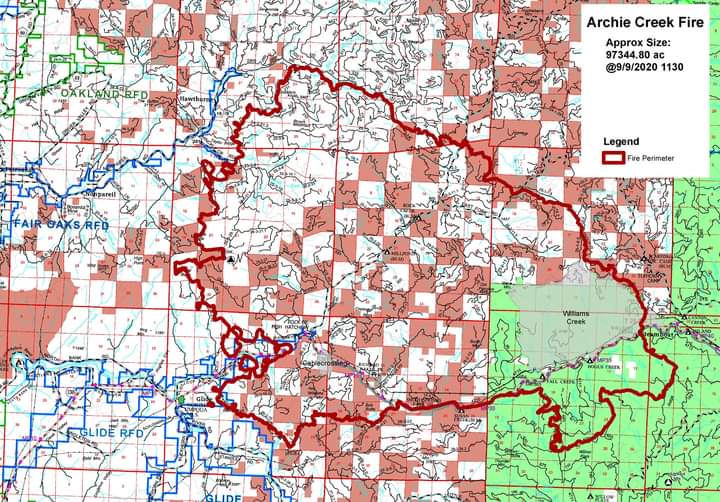

The fire lines weren’t even completed around the Archie Creek fire, and we still couldn’t see our neighbors’ houses through the smoke when the drumbeat of disinformation began to roll from the timber industry PR presses. Their message? The Labor Day fires caused unprecedented damage because of poorly managed federal forests. And when Donald Trump visited the California fires in September, the first words out of his mouth were “forest management,” followed by a denial of the influence of the worsening climate crisis on wildfire severity. Industry lobbyists had clearly earned their fat salaries.

Although unlogged forests typically have far higher fuel volumes, several peer-reviewed studies (e.g., Zald & Dunn, 2018; Thompson et al., 2007) have shown that plantations are far more flammable than old-growth forests. Clearcutting has also been shown to decrease summer stream flows by 50% for at least a half-century (Perry & Jones, 2017), leading to drier, more fire-prone forests. And another recent OSU-led study (Law, et al., 2018) has shown that forest harvest activities comprise Oregon’s biggest contribution to greenhouse gases. Although Big Timber has tried mightily to denigrate these studies through its taxpayer-supported propaganda machine known as the Oregon Forest Resources Institute1, the science is clear: clearcut/plantation forestry and climate neglect have set our communities on a collision course with fire.

All these phenomena came into play in Oregon’s Labor Day fires, including the Archie Creek fire in the North Umpqua watershed. Unprecedented hot, dry east winds drove power line-sparked fires towards our communities with speeds exceeding 50 mph. One hundred and nine homes were destroyed, priceless old-growth forests were lost, and millions of timber dollars went up in smoke.

Climate change has finally caught up with us, and we can expect more of these climate fires in the future.

Pull up Google Maps on your phone or computer and search for Archie Creek. Once there, switch to satellite view and look at the area between Steamboat and Glide. You will see that the fire mostly burned through vast plantations that now comprise the infamous “BLM checkerboard.” The 1 X 1 mile squares you see are a grid of public and private timberlands. You can identify the private lands because they are a mix of even-aged plantations (the “smooth,” uniform expanses) with virtually no old-growth forest left (the scattered dark green, “rough-looking” patches you can see on alternating BLM squares). But even on our public lands, you can see that a large percentage of our native forests have also been clearcut and converted to tree farms with very little old-growth forest left.

The Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER) maps created by federal agencies to identify severely burned areas show that these plantations suffered almost complete mortality. Surrounded by these human-made tinderboxes, even fire-resistant old-growth stands appear to have sustained major damage. But a cursory comparison of these two maps reveals that the few stands that did survive were unlogged forests on public lands. These have now become priceless repositories of the last vestiges of native genetic diversity left on this vast landscape.

The irony here is that forest management does indeed matter — industrial forest lands with their monoculture trees lined up like identical matchsticks are sitting ducks for wildfire, and the islands of remaining old-growth they surround are at far greater risk as a result. Industry’s claim that the small percentage of “poorly managed” public forests were somehow to blame for the unprecedented level of destruction would be laughable if not for the human tragedy involved.

So, what are the solutions going forward? Because this “new normal” has resulted from the confluence of local, regional, and global trends, it must be addressed at multiple scales.

First, we must finally address the ultimate cause of these wind-driven fires: climate change. Fortunately, the incoming administration has made the climate crisis a major focus of its campaign, and we can all join those efforts to forge a green economy that creates well-paying jobs while moving to a net-zero economy. But the “climate debt” is huge, and it will be a generation or more before we see the results of even the most ambitious initiatives.

At the other end of the scale, we need to accept that uncontrollable wildfires will be a part of living in the woods for the foreseeable future. Building a house in the forest comes with risks that must be acknowledged from the outset. But recent studies2 have shown that the 3 causes of ignition, 1) embers, 2) radiant heat, and 3) direct flame contact, can be mitigated with better building design and proper landscape maintenance. Just as we see in flood zones, Oregon’s building codes need to be upgraded in the fire-prone Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI), and our funding for Firewise communities must be maintained and increased.

That brings us back to wildland forest management. Many in the conservation community contend that we should focus solely on upgrading homes and managing vegetation in the WUI and that the backcountry should be left alone. While I agree that our priority should be protecting our friends and neighbors in the WUI, industrial management of immense swaths of our forests has left the small islands of native forest embedded within them at greater risk. The last remnants of the ancient forests that dominated our landscapes in the past store more carbon than any other forests on Earth. They are the last refuges of genetic diversity for the myriad species that depend on these habitats.

Old-time foresters used to refer to old-growth as “asbestos forests” because of their resilience to wildfire. But recent fires have shown that flames running through the crowns of even-aged plantations cause greater mortality to the old-growth stands they surround. While the need to protect homes in the WUI is immediate and urgent, the long-term protection of the last stands of our ancient forests is just as important to future generations. Therefore, it makes sense to manage the adjacent plantations to make them less likely to carry a crown fire.

While thinning dense plantations has in some cases increased their survival during wildfires, the pattern of thinning is important. Plantations thinned on a grid are less resistant to crown mortality than stands thinned an a more natural, patchy configuration (North, et al. 2018; Stone, et al. 2004). Recreating spatial heterogeneity in monoculture plantations will increase their resistance to wildfire and emulate natural patterns that also increase the diversity of habitats for a wider range of forest organisms, great and small. And thinning plantations will create jobs for forest workers, provide timber to local mills, and supply our nation the lumber it needs to rebuild areas recently devastated by wildfires and hurricanes.

This is a win-win opportunity — with the proper management of our natural resources, we can have safer, healthier forests AND a vibrant economy based on well-managed natural resources and the inspiring beauty of our forested landscapes.

Ken Carloni, Ph.D.

UW President, Education Chair

1See OPB/Oregonian article: https://www.opb.org/article/2020/08/04/oregon-forest-resources-institute-osu-timber-industry-investigation-lobbying/

See https://missoulacurrent.com/outdoors/2019/04/wildfire-jack-cohen/ and https://ucanr.edu/sites/fire/Prepare/Building/